A holistic approach to managing excess stomach acid leading to reflux

“Great news Mrs K…..your gastroscopy was completely normal!”, I smile over the table.

“Uhmm thanks Doc but I still have reflux symptoms” Mrs K replied.

Oh dear….let’s get to work!

The persistent heartburn. The burning sensation after meals. The sour taste waking them at 3am. The chronic throat clearing that won’t quit.

Have you just had a gastroscopy which was completely normal?

No ulcers, no Barrett’s, no cancer.

Just functional dyspepsia with reflux symptoms that refuse to improve despite a daily proton pump inhibitor (PPI).

Below are some safe and practical tips which may help you.

And unlike the long list of “trigger foods” everyone tells you to avoid: chocolate, coffee, citrus….these actually have randomised controlled trials backing them up.

Disclaimer 1: If you have persistent reflux symptoms, alarm features (difficulty swallowing, unintentional weight loss, vomiting blood), or symptoms lasting more than a few weeks, you need urgent investigation with gastroscopy +/- more. Don’t wait.

Disclaimer 2: This article is more geared towards people who have had a NORMAL gastroscopy but are still symptomatic. If you have new/concerning symptoms despite having a normal gastroscopy in the past follow disclaimer 1!

Disclaimer 3: Sorry nearly there! This is educational. Not specific advice for your reflux related symptoms. If you have concerns, speak to a professional.

Sorry…..the reason for so many disclaimers is reflux can mimic many other conditions which warrant appropriate/urgent investigations. This is geared for people who do not have red flag symptoms, have been appropriately investigated and want to improve through “lifestyle measures”.

*Deep breath* – all done, promise! Here we go.

(FYI – “GORD” = Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux Disease)

1. Sleep on your left side

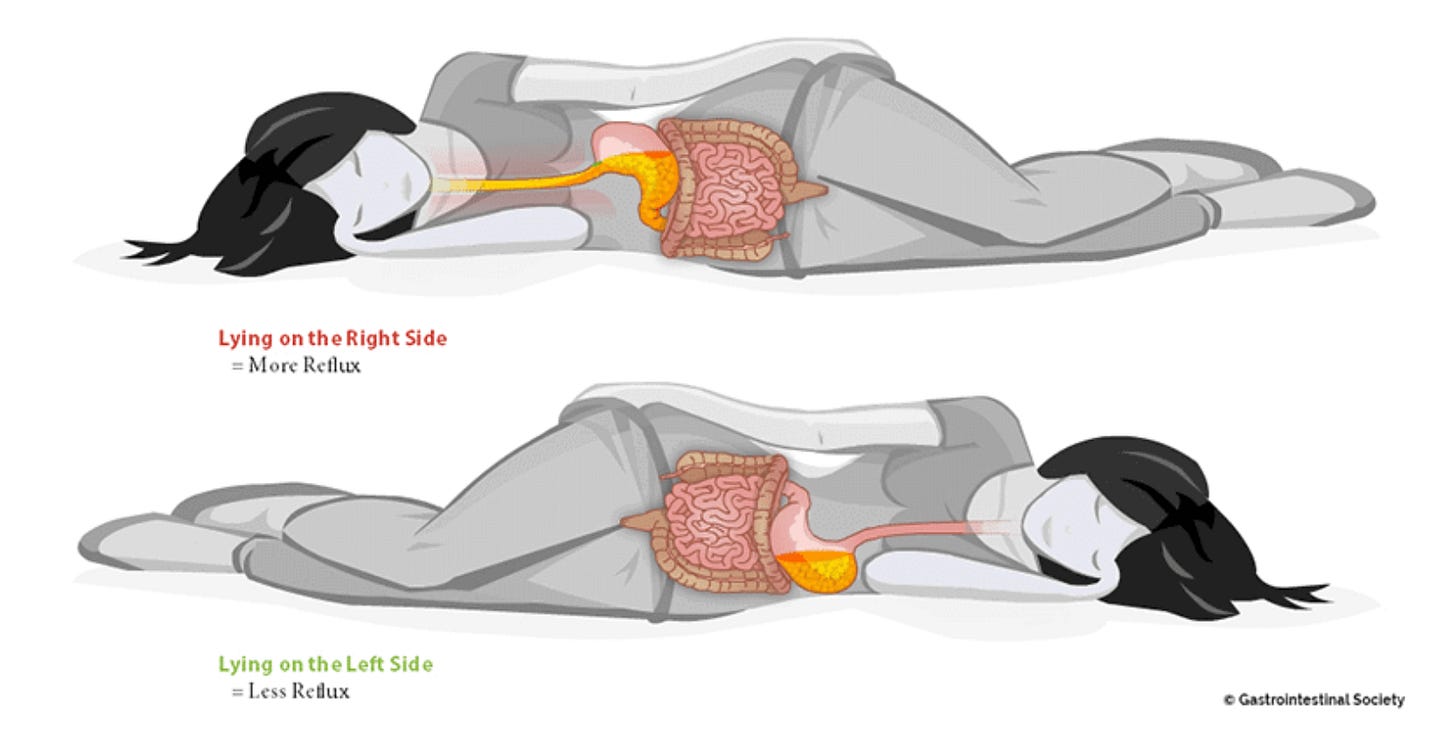

Your stomach is not symmetrical.

The fundus, that dome-shaped upper portion, sits in your upper left abdomen. When you sleep on your left side, the oesophagus sits above the gastric fundus. Gravity works in your favour. The acid pool stays away from the gastro-oesophageal junction.

Turn to your right side? Everything reverses. The oesophagus drops into a dependent position, sloping downward toward pooled acid. The lower oesophageal sphincter gets bathed in gastric contents. Reflux episodes increase. Acid clearance takes 2.5 times longer.

Sorry substack. A picture does speak a thousand words sometimes. https://badgut.org/information-centre/a-z-digestive-topics/heartburn-keeping-night/

A 2022 double-blind randomised controlled trial assigned 100 patients to electronic positional therapy devices that vibrated when they rolled onto their right side. The intervention group spent 61% of the night on their left side versus 39% for controls. The result? 44% achieved a 50% or greater reduction in nocturnal reflux symptoms compared to just 24% with sham devices.

That’s a 20% absolute improvement.

pH monitoring studies confirm this!

left lateral position reduces acid exposure time by 2-3% and cuts acid clearance time by ~80 seconds per episode.

The American College of Gastroenterology 2022 guidelines explicitly recommend avoiding sleeping right side down.

Simple. Get a body pillow. Train yourself left.

2. Eating habits: timing and portions

Stop eating three hours before bed

Your gastric acid secretion follows a circadian rhythm. Acid production peaks between 8 PM and midnight, exactly when many of us eat dinner and collapse onto the sofa.

Eating late creates a double burden: meal-stimulated acid secretion layered on top of your natural evening acid peak.

A 2005 case-control study of 441 people found that eating within three hours of bedtime increased GORD risk sevenfold.

The odds ratio was 7.45 (95% CI 3.38-16.4) compared to waiting four hours or more.

Another randomised crossover trial showed that eating two hours before bed versus six hours produced significantly more supine reflux (P=0.002). The effect was most pronounced in overweight patients and those with hiatal hernias.

Why? It takes roughly four hours for 90% of a solid meal to empty from your stomach.

Lie down before then and you’re fighting gravity with a stomach full of acid and food.

Your swallowing rate drops during sleep.

Saliva production, which normally contains acid-neutralising bicarbonate, plummets.

Your lower oesophageal sphincter pressure decreases. Every protective mechanism weakens while acid production surges.

The meal timing itself may be the only significant predictor of GORD recurrence after successful treatment.

Stop eating by 7 PM if you sleep at 10 PM. Stay upright. Let gravity and time do their work.

Netflix but you gotta chill

Smaller portions

Large meals distend your stomach. Kind of obvious but I need to say it.

However, this is not so obvious.

Gastric distention triggers transient lower oesophageal sphincter relaxations -TLESRs for short. These are the primary mechanism of reflux in most people. When you consume 750-1000 mL of food and liquid, TLESRs increase fourfold within the first ten minutes.

Smaller portions mean less mechanical pressure on the sphincter, faster gastric emptying, and less total acid load. Studies comparing high-calorie meals to lower-calorie meals show statistically significant differences in total oesophageal acid exposure time and number of reflux episodes.

Your stomach prefers smaller, more frequent ones.

3. Elevate the head of your bed

Gravity is your friend (kind of).

When you elevate the head of your bed by 15-20 centimetres (6-8 inches), you’re using basic physics to keep stomach acid where it belongs (in the…..stomach!)

The incline allows gravity to continuously pull gastric contents away from your oesophagus, even during those vulnerable sleeping hours.

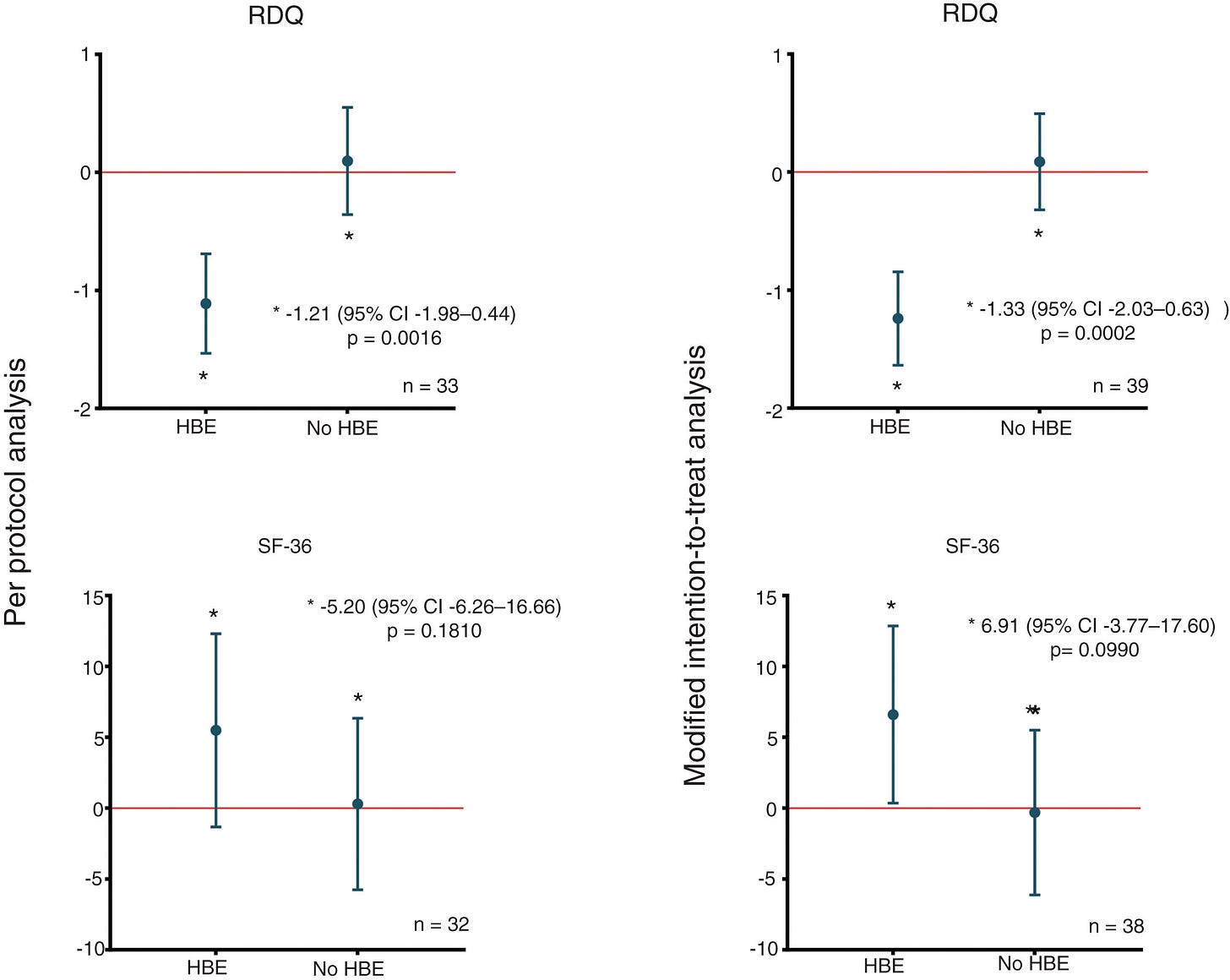

A 2020 randomised controlled trial (the IBELGA study) found that 69% of patients using 20cm bed elevation achieved clinically meaningful symptom improvement compared to just 33% in the control group. That’s more than double the response rate.

The patients were already on PPIs, making this improvement particularly impressive.

RDQ = Reflux disease questionnaire. HBE = Head bed elevation

A 2021 systematic review of controlled trials found that all four studies reporting on symptoms showed improvement with head-of-bed elevation. The physiological data backs this up: elevation reduces acid exposure time in the oesophagus, shortens acid clearance time when reflux does occur, and decreases the number of reflux episodes lasting longer than 5 minutes.

Sleep disturbances improved in 65% of participants.

The mechanics are straightforward. When you lie flat, your oesophagus and stomach are on the same horizontal plane. Any weakening of the lower oesophageal sphincter allows easy back flow.

With elevation, gravity assists oesophageal clearance; each swallow more effectively washes acid back into the stomach. The angle also reduces the likelihood of gastric contents reaching the gastro-oesophageal junction.

Use bed blocks under the head of your bed frame…..not just extra pillows, which can actually worsen reflux by bending you at the waist and increasing abdominal pressure.

Foam wedges work too, though some find them less comfortable for all-night use. The key is maintaining that consistent 15-20cm elevation of your entire upper body.

Yes, there are minor inconveniences. Some patients report initial sleep disruption or sliding down during the night.

One study diplomatically noted “sexual activity interference” as a potential issue.

But unlike medications with their long lists of side effects and potential long-term risks, these are manageable adjustments. It’s cheap, safe, and backed by randomised controlled trials.

4. Stop smoking

If you smoke, this might be your most powerful lever for improvement.

Smoking directly weakens your lower oesophageal sphincter, reducing pressure chronically and causing an increased rate of reflux events.

The effect is immediate and dramatic…lower oesophageal sphincter pressure drops by 20% while actively smoking a cigarette.

Nicotine is the culprit, making it easier for stomach acid to escape into the oesophagus. Smoking decreases saliva production and its bicarbonate content, which normally helps neutralise acid.

This prolongs oesophageal acid clearance time. Most reflux events in smokers occur through the “abdominal strain mechanism”; coughing and deep inspiration cause sudden increases in intra-abdominal pressure that overwhelm the weakened sphincter.

Those smoking 10-20 pack-years have nearly triple the risk of reflux oesophagitis and the risk remains elevated even in former smokers with more than 20 pack-years.

A 2024 population study of 9,631 adults found Gastro-oesophageal Reflux Disease (GORD) prevalence was 23% higher in smokers versus non-smokers.

E-cigarettes and vaping carry similar risks…nicotine from any source weakens the oesophageal sphincter and increases reflux frequency. Even secondhand smoke exposure can impair sphincter function.

If you’re serious about controlling reflux without medication, smoking cessation is essential.

I know…easy said than done. But if you have reflux and you smoke, this must be your first step.

5. Lose weight (if you’re overweight)

The intervention with a strong recommendation from the American College of Gastroenterology based on moderate-quality evidence. UK guidelines are similar.

Obesity increases GORD risk through multiple mechanisms: increased intra-abdominal pressure from visceral fat physically compresses your stomach, promoting reflux.

Excess weight is associated with hiatal hernia formation. It decreases lower oesophageal sphincter pressure and increases TLESRs.

And visceral adipose tissue secretes pro-inflammatory adipokines (leptin, TNF-α, IL-1β) that may impair oesophageal mucosal barrier integrity.

A landmark 2013 study enrolled 332 overweight and obese subjects in a structured six-month weight loss program. Average weight loss: 13 kg. GORD prevalence dropped from 37% to 15%. Eighty percent had symptom reduction; 65% achieved complete resolution.

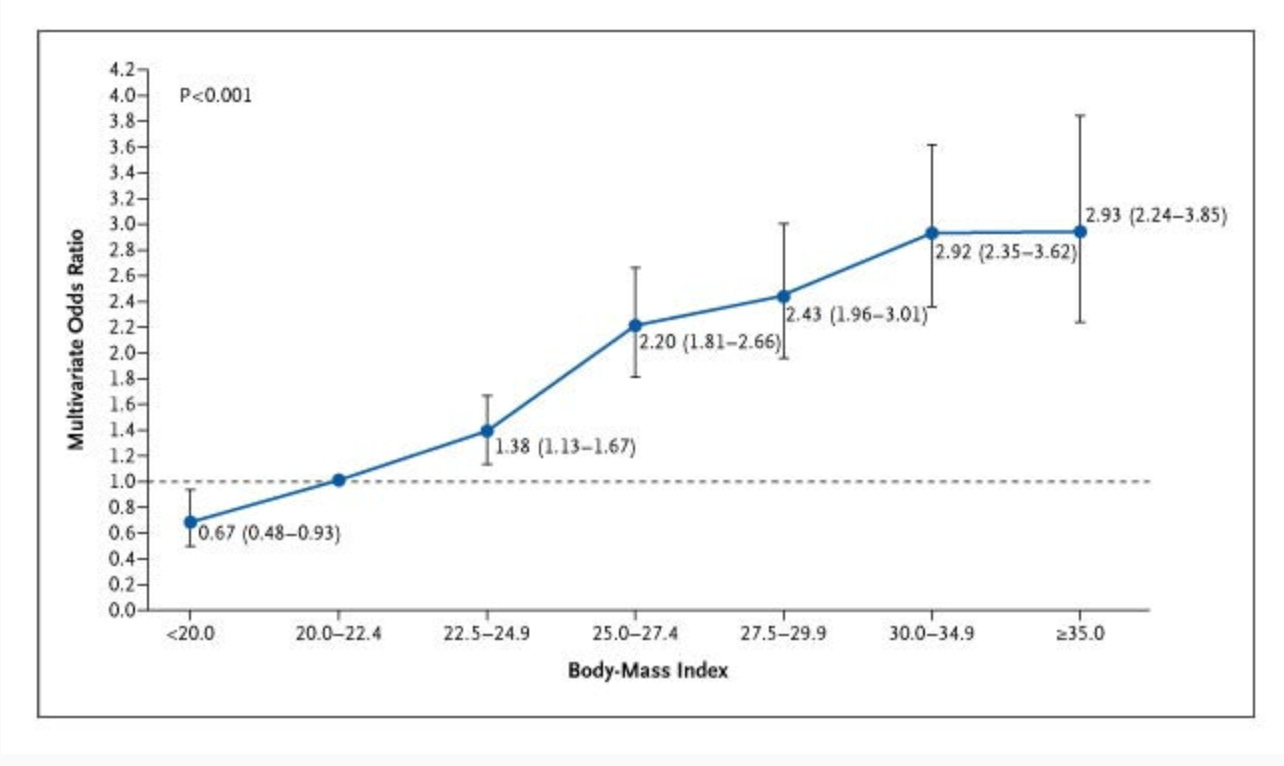

Even in normal-weight individuals, every increase in BMI category increases GORD risk. Meta-analyses show overweight individuals have a 1.43 times higher risk of GERD; obese individuals have nearly double the risk.

Another study showed that 50% of patients who lost weight could completely discontinue their PPIs. Another 32% could halve their dose.

Weight loss works. It’s not easy. But it works.

Association between Body-Mass Index and the Risk of Frequent Symptoms of Gastro-oesophageal Reflux Disease.

The GLP-1 paradox

Here’s where it gets interesting.

GLP-1 receptor agonists, semaglutide, tirzepatide, liraglutide, are revolutionising obesity treatment.

Read my thoughts here

But there’s a catch. GLP-1s slow gastric emptying profoundly. They delay the stomach’s ability to clear food and acid. A 2025 meta-analysis of 55 RCTs involving over 106,000 participants found GLP-1s increased GORD risk two fold.

Short-acting formulations are worse than long-acting ones. Recent use is riskier than chronic use, which shows tachyphylaxis.

So we have a paradox: a medication that worsens reflux through delayed gastric emptying but simultaneously treats one of its root cause (obesity) through dramatic weight loss.

The clinical balance depends on the individual.

For someone with severe obesity and mild GORD, the long-term weight loss benefits likely outweigh short-term gastric emptying effects. For someone with severe erosive oesophagitis, a stomach ulcer or Barrett’s oesophagus, the risks may exceed the benefits.

There are no simple answers. Speak to your health professional.

There you have it

I’m not suggesting you never enjoy a late dinner or that you obsess over sleeping position.

Life needs joy, and food is part of that. But armed with this evidence, you can make informed choices.

Sleep left. Elevate the head of your bed. Finish eating by 7 PM. Keep portions reasonable. Stop smoking if you smoke. Consider weight loss if you’re carrying extra weight.

And if your doctor suggests a GLP-1 for obesity, have an honest conversation about your reflux history.

Small changes compound over time. Not all of them require a prescription.

Struggling with liver or digestive issues that affect your daily life? Invest in your gut health with a private, personalised consultation where I will explore your specific symptoms and develop a targeted treatment plan. Take the first step toward digestive wellness today: https://bucksgastroenterology.co.uk/contact/

References

- Simadibrata DM, et al. The Efficacy of Left Lateral Decubitus Sleep Position on Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World J Clin Cases. 2023;11(30):7329-7336.

- Schuitenmaker JM, et al. Sleep Positional Therapy in Patients With Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Randomized Trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(10):2315-2323.

- Khoury RM, et al. Influence of Spontaneous Sleep Positions on Nighttime Recumbent Reflux in Patients With Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(8):2069-73.

- Katz PO, et al. ACG Clinical Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(1):27-56.

- Fujiwara Y, et al. Association Between Dinner-to-Bed Time and Gastro-Esophageal Reflux Disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(12):2633-6.

- Piesman M, et al. Nocturnal Reflux Episodes Following the Administration of a Standardized Meal: Does Timing Matter? Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(10):2128-34.

- Moore JG, Englert E. Circadian Rhythm of Gastric Acid Secretion in Man. Nature. 1970;226:1261-1262.

- Albarqouni L, et al. Head of Bed Elevation to Relieve Gastroesophageal Reflux Symptoms: A Systematic Review. BMC Fam Pract. 2021;22(1):24.

- Person E, et al. Impact of Head of Bed Elevation in Symptoms of Patients with Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Randomized Single-Blind Study (IBELGA). Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;43(6):310-316.

- Khan BA, et al. Effect of Bed Head Elevation During Sleep in Symptomatic Patients of Nocturnal Gastroesophageal Reflux. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27(6):1078-82.

- Kahrilas PJ, Gupta RR. Mechanisms of Acid Reflux Associated With Cigarette Smoking. Gut. 1990;31(1):4-10.

- Dennish GW, Castell DO. Inhibitory Effect of Smoking on the Lower Esophageal Sphincter. N Engl J Med. 1971;284(20):1136-1137.

- Fujiwara Y, et al. Long-Term Benefits of Smoking Cessation on Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Health-Related Quality of Life. PLOS ONE. 2016;11(2):e0147860.

- Watanabe Y, et al. The Association Between Smoking Exposure and Reflux Esophagitis: A Cross-sectional Study. Internal Medicine. 2024;63(1):45-52.

- Singh M, et al. Weight Loss Can Lead to Resolution of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Symptoms: A Prospective Intervention Trial. Obesity. 2013;21(2):284-90.

- Jacobson BC, et al. Body-Mass Index and Symptoms of Gastroesophageal Reflux in Women. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(22):2340-8.

- Hampel H, et al. Meta-Analysis: Obesity and the Risk for Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Its Complications. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(3):199-211.

- Valentini A, et al. Dietary Weight Loss Intervention Provides Improvement of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Symptoms—A Randomized Clinical Trial. Clin Obes. 2023;13(1):e12556.

- Noh Y, et al. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists and Risk for Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med. 2025;178(9):1268-1278.

- Liu BD, et al. Shorter-Acting Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists Are Associated With Increased Development of Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux Disease and Its Complications. Gut. 2024;73(2):246-254.

- Gastroenterology. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists and Gastrointestinal Adverse Events: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 55 RCTs. Gastroenterology. 2025;S0016-5085(25)00845-5.

General Disclaimer

Please note that the opinions expressed here are those of Dr Hussenbux and do not necessarily reflect the positions of Buckinghamshire Healthcare NHS Trust. The advice is intended as general and should not be interpreted as personal clinical advice. If you have problems, please tell your healthcare professional, who will be able to help you.