Otherwise known as Decompensated Liver Cirrhosis

The liver can take a beating.

However even one of the most resilient organs with extraordinary regenerative processes has its limits…

When chronic insult (through metabolic syndrome, alcohol or untreated viral (hepatitis B or C) or autoimmune hepatitis) overwhelms the healing mechanisms, normal liver cells (hepatocytes) become fibrosed which eventually leads to cirrhosis.

As a result the liver starts to decompensate…..let’s discuss!

General disclaimer: There will be a bit more jargon than my typical post (sorry, not sorry). And please note, decompensated liver cirrhosis is a small portion of liver disease.

The main enemy for the vast majority of people is Fatty Liver….read my guide to reverse it here

Once diagnosed with decompensated liver cirrhosis survival plummets from over 10 years to approximately 2 years.

Three major complications emerge that signal advanced disease:

- Ascites (abdominal fluid accumulation)

- Hepatic encephalopathy (brain dysfunction)

- Variceal bleeding (ruptured oesophageal blood vessels).

These complications arise from portal hypertension – increased pressure in the liver’s blood vessels – which affects over 90% of patients with cirrhosis and fundamentally alters how blood flows through the body.

The transition from compensated to decompensated cirrhosis occurs in approximately 5-7% of patients annually, transforming a manageable chronic condition into a life-threatening emergency.

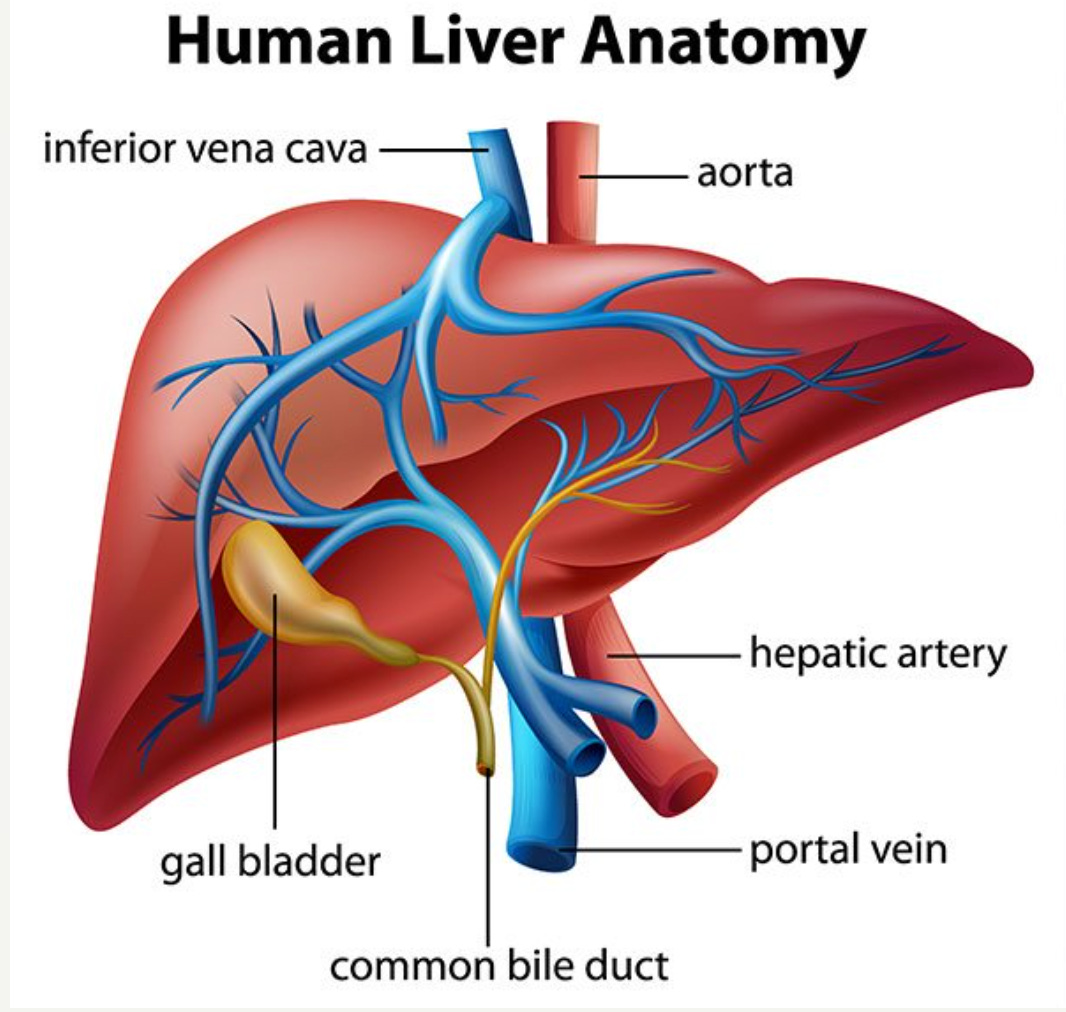

??Portal Hypertension??

The journey toward decompensated cirrhosis begins with portal hypertension….

There is an elevated pressure within the portal venous system that drains blood from the digestive organs to the liver.

Portal pressure normally ranges from 1-5 mmHg, but in cirrhosis it can exceed 20 mmHg…this elevation alters cardiovascular physiology.

This elevated pressure results from two synergistic factors:

- increased resistance within the scarred liver and

- paradoxically increased blood flow into the portal system.

The scarred liver creates both fixed structural resistance from fibrotic tissue and regenerative nodules, plus dynamic resistance from activated hepatic stellate cells.

Simultaneously, the body develops a hyperdynamic circulation characterised by splanchnic vasodilation – the blood vessels supplying the intestines dilate dramatically, increasing portal blood flow by up to 50%.

This creates a vicious cycle where elevated pressure forces blood to find alternative pathways back to the heart, forming portosystemic collaterals; essentially bypass routes that decompress the portal system but create new problems.

When portal pressure reaches 10 mmHg, varices begin forming; at 12 mmHg, ascites develops and bleeding risk becomes significant.

Portal hypertension grade directly correlates with survival. Patients progress through four distinct stages, with one-year mortality increasing from 1% in compensated disease without varices to 57% when variceal haemorrhage occurs alongside ascites.

https://www.vascularcures.org/portal-hypertension

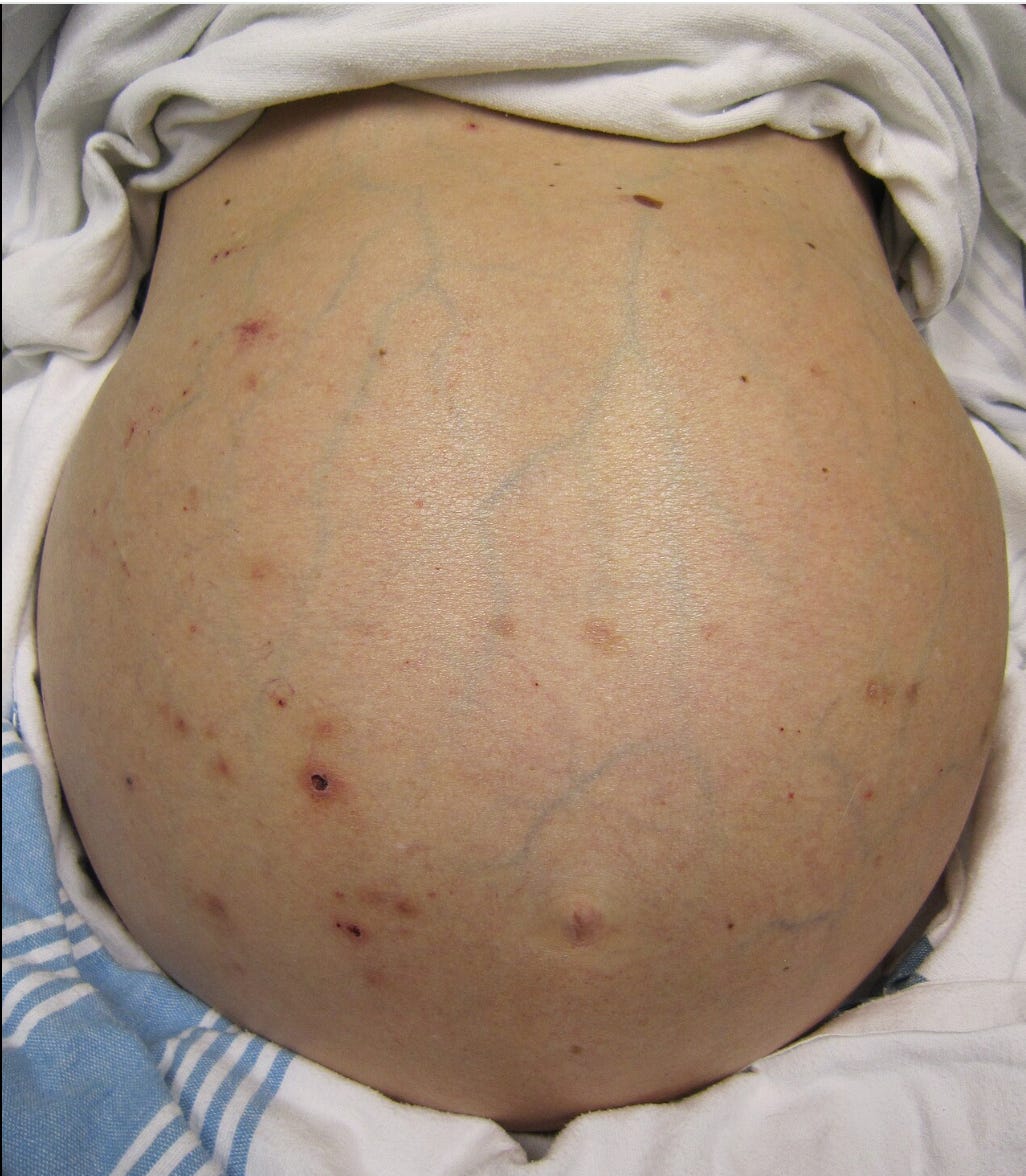

Warning Sign 1: Ascites

Ascites is pathological accumulation of fluid in the abdominal cavity. This critical transition point is where one-year mortality jumps from under 5% to 15-20%. The cause involves a complex interplay of haemodynamic, hormonal, and lymphatic mechanisms that create fluid retention.

The primary mechanism begins with severe portal hypertension exceeding 12 mmHg, which triggers splanchnic vasodilation and creates what clinicians term “effective arterial blood volume depletion.” Despite the patient being fluid-overloaded, the body perceives volume depletion due to massive arterial dilation, activating powerful compensatory systems including the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and sympathetic nervous system.

These hormonal responses drive aggressive sodium and water retention by the kidneys while simultaneously increasing lymph production in the liver and intestines beyond the lymphatic system’s drainage capacity of approximately 850ml daily. The excess lymph essentially leaks into the abdomen (peritoneal cavity), creating the characteristic abdominal swelling.

Clinically, patients notice progressive abdominal distention, early satiety (full up quicker), and shortness of breath. Physical examination reveals shifting dullness to percussion – a reliable sign when fluid volume exceeds 1500ml.

Weight gain often precedes visible swelling, with patients gaining 1-2 kilograms rapidly over days.

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis represents ascites’ most dangerous complication, occurring through bacterial translocation from the intestinal tract. Portal hypertension increases intestinal permeability while simultaneously impairing immune function, creating ideal conditions for bacterial seeding of ascitic fluid.

The most common organisms include Escherichia coli (60% of cases) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (15-20%).

The mortality statistics are sobering: patients developing ascites face 40-50% mortality within two years, with refractory ascites carrying even worse prognosis at under 50% one-year survival. When SBP develops, in-hospital mortality ranges from 10-46%, with long-term mortality reaching 44-70% at one year despite treatment advances. Bad news.

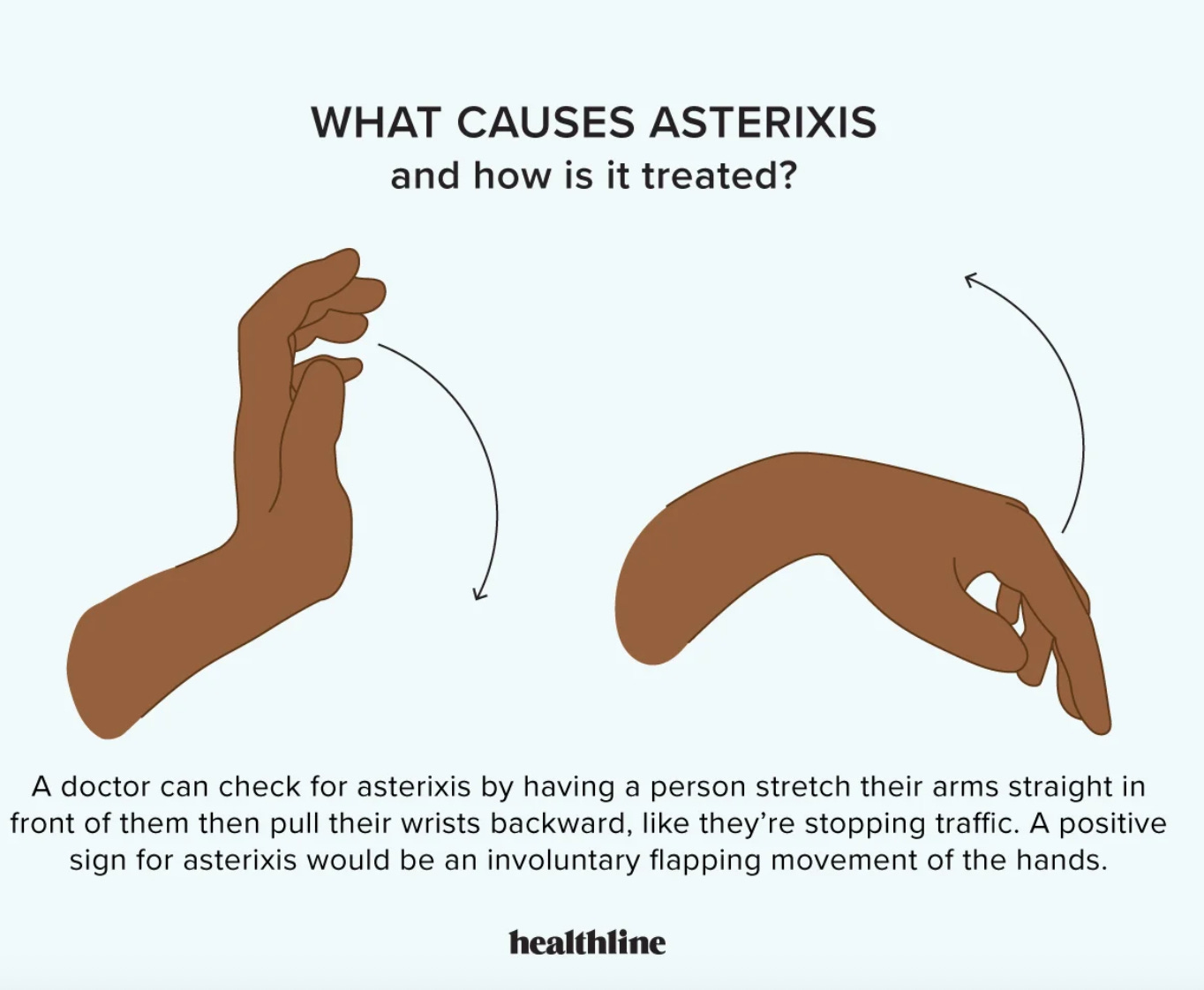

Warning Sign 2: Hepatic Encephalopathy

A warning sign of hepatic encephalopathy

Hepatic encephalopathy affects 35-45% of cirrhotic patients and represents one of the most feared complications, manifesting as a spectrum of neuropsychiatric abnormalities ranging from subtle cognitive deficits to deep coma. The pathophysiology centere on ammonia toxicity, though multiple mechanisms contribute to this complex syndrome that can progress rapidly from minor confusion to life-threatening brain swelling.

Under normal circumstances, the liver efficiently detoxifies ammonia – a toxic byproduct of protein metabolism, by converting it to urea through the hepatic urea cycle.

In cirrhosis, this detoxification system fails through two mechanisms:

- direct hepatocellular dysfunction reduces the liver’s processing capacity

- portosystemic shunting allows ammonia-rich portal blood to bypass hepatic metabolism entirely, delivering toxic levels directly to the brain.

Astrocytes – the brain’s ammonia-detoxifying cells – become the primary victims, converting excess ammonia to glutamine. This creates a “Trojan horse” mechanism: glutamine accumulates causing cell swelling, while also generating more intracellular ammonia and oxidative stress.

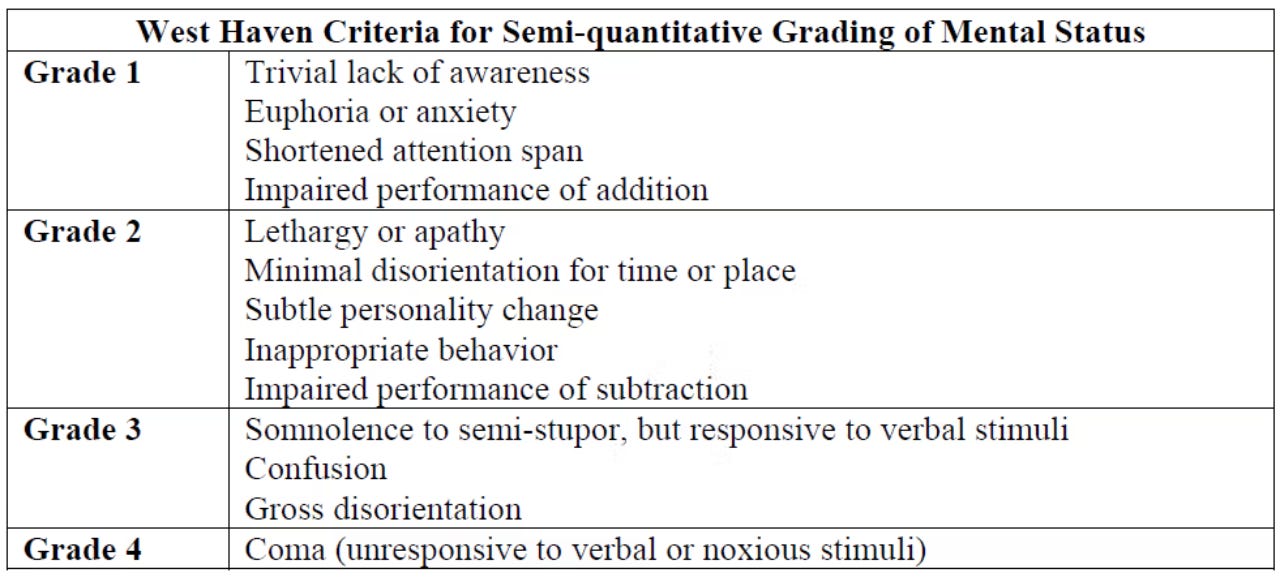

The West Haven Criteria provide standardised staging that directly correlates with prognosis:

Patients with grades 1-2 have relatively preserved survival, while grades 3-4 carry 90-day mortality rates of 24% compared to under 10% for milder grades. Perhaps most importantly, episode duration exceeding 48 hours significantly worsens prognosis – 28-day survival drops from 88.9% to 67.2% when episodes persist beyond this critical threshold.

Warning sign 3: Variceal bleeding

Osophageal variceal bleeding represents the most immediately life-threatening complication of portal hypertension, occurring when enlarged veins in the oesophagus rupture under extreme pressure. These dilated vessels form as the body attempts to decompress the high-pressure portal system, creating fragile collateral pathways with thin walls prone to catastrophic bleeding.

The oesophagus with grade 1 (left) grade 2 (middle) and grade 3 (right) varices

Endoscopic features directly predict bleeding risk through well-validated classification systems. Large varices (F2-F3 grade) carry 15% annual bleeding risk compared to 5% for small varices. The presence of “red signs” – including red wale markings and cherry-red spots indicating wall thinning – dramatically increases rupture risk even in smaller varices and mandates preventative (or prophylactic) treatment.

The clinical presentation is often dramatic and unmistakable: haematemesis (vomiting blood) occurs in 70-80% of cases, accompanied by melaena (black, tarry stools) as blood is digested during intestinal transit. The hemodynamic consequences can be catastrophic, with patients developing hypovolaemic shock, altered mental status, and circulatory collapse within minutes to hours.

The mortality statistics: first episode mortality ranges from 10% in early liver disease to over 70% in advanced stages, with overall six-week mortality of 15-20% using current standard therapy. In-hospital mortality ranges from 13.4-22.7%, while patients face immediate 20% mortality risk from their first bleeding episode.

Long-term prognosis remains grim even for survivors: one-year survival is only 50% in patients with cirrhosis and variceal bleeding, dropping to just 27.7% at ten years. The median survival from time of variceal diagnosis is approximately 59 months.

Ok that was scary

Compensated cirrhosis patients have relatively normal life expectancy with five-year survival around 80% and ten-year survival near 70%. However, the development of any decompensating complication fundamentally alters this trajectory.

These warning signs represent medical emergencies requiring immediate hepatology consultation. While manageable short-term, they signify fundamental liver disease that typically progresses to death without transplantation and/or specialist input. Recognising when compensated disease crosses into life-threatening decompensation enables timely intervention; the difference between years of life and imminent mortality.

Struggling with digestive issues that affect your daily life? Invest in your gut health with a private, personalised consultation where I will explore your specific symptoms and develop a targeted treatment plan. Take the first step toward digestive wellness today: https://bucksgastroenterology.co.uk/contact/

References

- EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Journal of Hepatology. 2018;69(2):406-460.

- D’Amico G, Garcia-Tsao G, Pagliaro L. Natural history and prognostic indicators of survival in cirrhosis: A systematic review of 118 studies. Journal of Hepatology. 2006;44(1):217-231.

- Runyon BA. Management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis: An update. Hepatology. 2009;49(6):2087-2107.

- Biggins SW, Angeli P, Garcia-Tsao G, et al. Diagnosis, evaluation and management of ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and hepatorenal syndrome: 2021 practice guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2021;74(2):1014-1048.

- Vilstrup H, Amodio P, Bajaj J, et al. Hepatic encephalopathy in chronic liver disease: 2014 Practice Guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the European Association for the Study of the Liver. Hepatology. 2014;60(2):715-735.

- Garcia-Tsao G, Abraldes JG, Berzigotti A, Bosch J. Portal hypertensive bleeding in cirrhosis: Risk stratification, diagnosis, and management: 2016 practice guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2017;65(1):310-335.

- Arroyo V, Moreau R, Jalan R, Ginès P. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: A new syndrome that will re-classify cirrhosis. Journal of Hepatology. 2015;62(1):S131-S143.

- Trebicka J, Fernandez J, Papp M, et al. The PREDICT study uncovers three clinical courses of acutely decompensated cirrhosis that have distinct pathophysiology. Journal of Hepatology. 2020;73(4):842-854.

- Singal AK, Bataller R, Ahn J, Kamath PS, Shah VH. ACG Clinical Guideline: Alcoholic Liver Disease. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2018;113(2):175-194.

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. Journal of Hepatology. 2017;67(2):370-398.

- Devarbhavi H, Asrani SK, Arab JP, et al. Global burden of liver disease: 2023 update. Journal of Hepatology. 2023;79(2):516-537.

- Wong F, Reddy KR, O’Leary JG, et al. Impact of chronic kidney disease on outcomes in cirrhosis. Liver Transplantation. 2019;25(6):870-880.

- Ferenci P, Lockwood A, Mullen K, et al. Hepatic encephalopathy–definition, nomenclature, diagnosis, and quantification: final report of the working party at the 11th World Congresses of Gastroenterology, Vienna, 1998. Hepatology. 2002;35(3):716-721.

- de Franchis R, Baveno VI Faculty. Expanding consensus in portal hypertension: Report of the Baveno VI Consensus Workshop: Stratifying risk and individualizing care for portal hypertension. Journal of Hepatology. 2015;63(3):743-752.

- Ginès P, Quintero E, Arroyo V, et al. Compensated cirrhosis: natural history and prognostic factors. Hepatology. 1987;7(1):122-128.

General Disclaimer

Please note that the opinions expressed here are those of Dr Hussenbux and do not necessarily reflect the positions of Buckinghamhsire Healthcare NHS Trust. The advice is intended as general and should not be interpreted as personal clinical advice. If you have problems, please tell your healthcare professional, who will be able to help you.